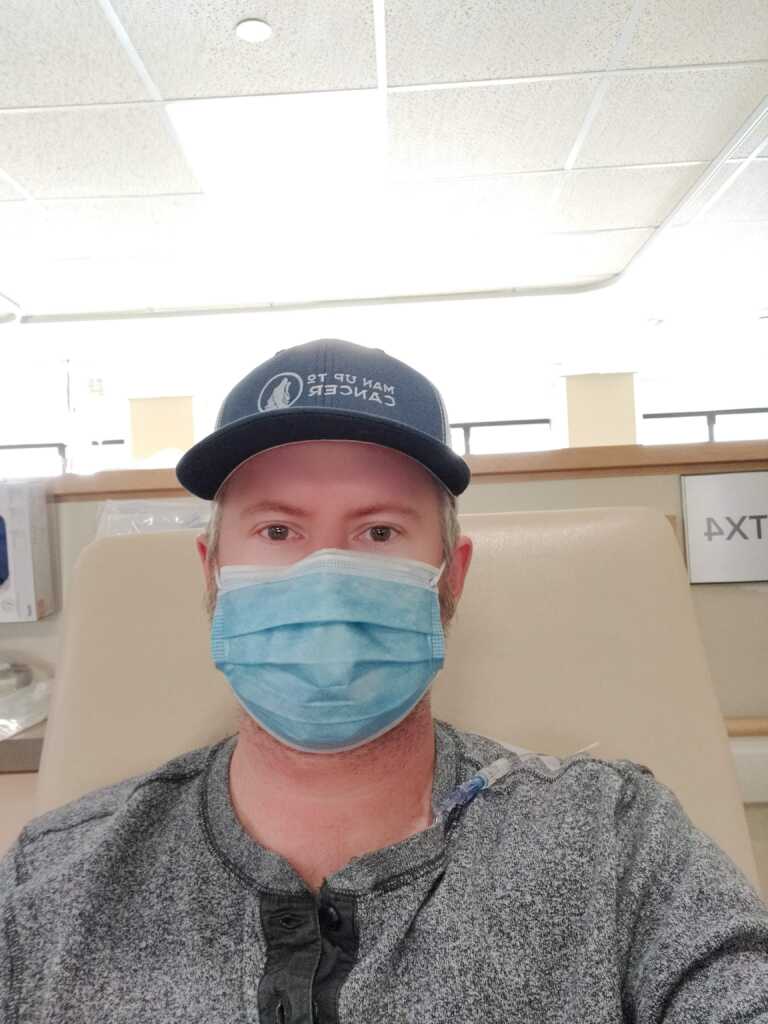

Sitting in the chemotherapy unit, I can’t help but look around at the different people who find themselves in such a terrible place.

Here, under the glow of mismatched fluorescent lights, between the clinical, beige walls of the hospital, people are fighting for their lives.

In spite of the analogues made between cancer and war, it doesn’t much look like a fight. Dozens of patients and caregivers sit patiently, faces buried in TVs, phones, and tablets as medication slowly flows. If this is a war, it is overtly mundane. Aside from the odd reaction to the medication, not much goes on in the chemo suite.

As people sit around, waiting for their cycle to finish, the nurses chatter away about scheduling, interdepartmental and administrative shenanigans, and exchange lighthearted jokes with patients. They don and doff their gowns and PPE as they move from patient to patient, fiddling with cytotoxic IVs.

I could say that there are people of all ages, but that would be untrue. The majority of people are middle-aged or older. At 34, I’m consistently the youngest person in the room. It’s not a chatty crowd. Even if folks wanted to talk, I don’t know where we’d find common ground.

Most people, even the caregivers, sit in silence, waiting for the treatment cycle to end. Some only have to stay for 15 minutes. Others have to spend 8 hours. Most are somewhere in between. It’s an unexciting place.

Over the roaring sound of crappy daytime television, people pass the time. There are no headphones. Each chair has its own TV. It’s akin to being on a long flight where everyone is watching what they want, at full volume, without regard to anyone else sharing the space.

I like to use my time in the chemo suite to sleep or to sit and reflect. It’s one of the few opportunities to just be, absent from any of life’s regular pressures. It’s the one place where it actually feels like I’m a cancer patient. To me, it’s both traumatic and healing.

Each time I make my way to treatment, it makes me feel sick to my stomach. There’s an anticipation for how terrible I’ll feel afterwards. There’s apprehension that this could be the cycle where I have a serious reaction, stop breathing, or end up in the ICU. Having no prior reaction to chemotherapy drugs does not guarantee the same outcome each time.

Once the medication starts to flow and no reaction comes, the nausea fades. Things start to feel therapeutic. It’s counterintuitive, but once you can feel the effects of the medication, it also provides comfort that it’s working. It’s a constant balance between anticipating the fatigue and side effects while feeling that the medication is doing its job.

Side effects and feeling the drugs enter your system are no guarantee that the medication is actually working, but it’s a tangible thing that provides comfort. When you can feel the changes to your body in real time, it’s accompanied by a sense of comfort.

I’m sure I’m not alone in feeling how I do about treatment. It’s really just boring more than anything.

When I finish my rotation through the chemo suite, I don’t think I’ll miss this place. I’ll miss the healthcare workers who’ve so diligently overseen my care over my six month course of treatment.

“Thank you, but I hope I never see you again,” I’ll say, meaning it wholeheartedly.

If I never set foot in the chemo suite again, I’ll be a happy camper.