Trigger Warning: this gets into some statistics and details that some may find distressing. Maybe don’t read it if you’re not into knowing statistics or a breakdown of the specifics related to my cancer.

I didn’t know going into my cancer experience just how many appointments there would be. There are some weeks where it’s basically a part-time job. I mean that in the literal sense: I’ve had weeks where there have been up to 14 hours of appointments, waiting around, and cancer-related errands.

With so many appointments and professionals involved, you’d think that it would be straightforward enough to know whether chemotherapy is having a positive effect. But cancer treatment, like the disease itself, is complex and—at times—unpredictable. Sure, there are statistics (which are scary as hell) and likelihoods that help inform outcomes, but the efficacy on a case-by-case basis is variable and only so predictable.

I’m asked often if I know whether treatment is working.

It’s exceptionally hard to tell.

I’ve developed some new symptoms, so I have some scans planned to see if I’ve had spread during treatment. The problem is that the symptoms I’m experiencing are also side effects of some of the medications that I’m taking, so it’s anyone’s guess what’s going on.

Like I said. Complicated.

The unseen

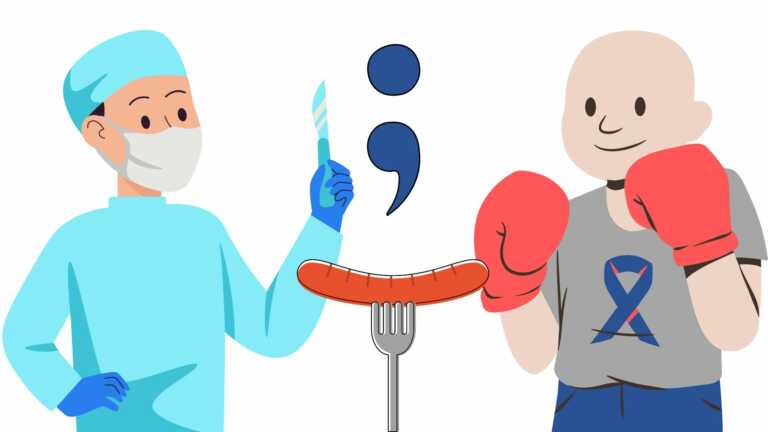

As many know by now, I’m being treated with clean-up chemotherapy. I’m in a state where there’s no visible cancer left in my body. The physical tumour has been removed (along with a few sausage links worth of bowel) and the chemotherapy is intended to kill off the cellular vestiges which, unchecked, can so quickly begin dividing, growing, and causing new tumours to form. Of course, there is a lot of collateral damage since the chemotherapy attacks my healthy cells, too.

Since there are no visible tumours, it may seem that I’m limbo: Do I still have cancer, or not?

The answer is yes.

Specifically, I have locally-advanced colon cancer. It has not spread to other organs, however, it has spread in the area near the colon as well as some nearby lymph nodes which have been removed.

Waiting is a necessary evil

Scans and symptoms aside, there’s really no way to tell if treatment is working. Some folks can get a rough idea based on blood work, but I’m not in that camp.

There’s a protein in the blood called carcinoembryonic antigen (CEA) which can be an indicator that there is more or less cancer. My CEA has been normal this whole time, so it hasn’t been a helpful indicator for me, even from the outset.

So now I just wait for my next round of scan results and to see if new symptoms crop up.

How is prognosis measured?

There are so many ways in which cancer is talked about, but as a patient, I care about two things:

Progression-free survival, which is the probability that I’ll remain disease-free after a given period of time. This answers the question: “What is the likelihood that the cancer will spread?”

Overall survival, which is the probability that I’ll be alive after five years. This aims to answer the question: “Will cancer kill me?”

It’s overwhelming to think that surviving five years is a marker of success when you’ve been diagnosed at 34. Yet, here we are.

How is success measured?

During a conversation I was having the other day, someone said something that resonated:

“You’ll know treatment was successful when you die from something other than cancer.”

While sarcastic, it’s also true.

Success is measured in years

I’m going to level with you.

It’s going to be uncomfortable.

I have a form of colon cancer with a bleak prognosis.

In fact, I kind of have a perfect storm of issues that are all stacked together into a giant shit sandwich of a diagnosis.

Here’s a breakdown of some of the ways the deck is stacked against me:

- My tumour was a mucinous adenocarcinoma. Between 10-20% of colorectal cancer is mucinous. This predisposes me to a much lower chance for progression-free survival. Mucinous colon cancer is more likely to spread to the lining of my abdominal cavity (the peritoneum) and to lymph nodes beyond the primary tumour site. At my time of surgery in March, there was already minor spread to the peritoneum and lymph nodes, which doubled the length of my surgery (they got it all, probably).

- My cancer has invaded the structure of my nervous system. This perineural invasion exposes me to a higher risk of the cancer spreading to other areas. This is not new and was present when I had my bowel resection in March, but remains a factor.

- My cancer includes signet-ring cells. These little shits are filled with mucin and don’t stick together. This means that they’re floating around, taking up space between healthy cells, trying to kill me. Not all colon cancer involves these types of cancer cells, which are especially resistant to chemotherapy.

What’s the prognosis?

This is the hard part to gauge. I’m not a statistic, but also need to be realistic about how survivorship has gone for other people like me. There’s no nuance to the stats. They simply are.

For every 100 patients like me, just 38 will remain disease free after three years. At the five year mark, that number shrinks to 30 of every 100.

These are uncomfortable numbers to be dealing with, but are based on stage IIIC (specifically T4a N2a M0) aggregates from one of the top cancer centres in the United States. They also don’t consider the nuances of my specific cancer.

In short: If I make it three years without the disease progressing, I’ll have beaten the odds.

Still, my treatment is intended to be curative. Time will tell if and for how long.

How does colon cancer progress, anyways?

The main avenue for progression is via the lymphatic system, which drains fluids in the body that are leaked via blood vessels (this is a gross oversimplification). This reaches all over the body. I’ve included a diagram.

When colon cancer metastasizes, it typically spreads to the the liver or lungs. The odd time, it will scoot up to the brain. It could also decide to come back in my remaining bowel.

Of course, there are some exceptions to this. As I mentioned: cancer is unpredictable.

So, once chemotherapy is over, I’ll be moving to the surveillance phase which includes keeping an eye on the organs and areas mentioned above. CTs, MRIs, and a colonoscopy are in the cards.

Progression doesn’t necessarily mean it’s incurable

Something that is, as far as I know, fairly unique to colon cancer is that even if spread occurs, there are additional treatments undertaken with the intent to cure.

It just depends where it spreads to.

People get their liver hacked up, or lungs blasted with radiation. It can cure the cancer.

Like everything else about this disease, it all just depends on where and what happens.

What’s next?

As I write this, I’m just past the halfway mark on my planned chemotherapy cycles.

I’ll stay the course, which should have me finishing up treatment toward the end of November or early December.

Every two weeks, I’ll sit in the chair, continue to have poison pumped through my veins, and simply wait until my next series of scans to see if anything has changed. I’m still getting full strength Oxaliplatin + 5-FU, which is the best medicine available to me.

I’ll have some CT scans in a couple of weeks, which will put my mind at ease one way or the other.

In the meantime, I’ll just keep on keeping on. Because that’s what I can do.