The last time I wrote something, I shared that I was pursuing a clinical trial involving a chemotherapy pump that will deliver drugs straight into my liver.

As someone with advanced colon cancer, this option is available to me under a very strict set of circumstances. I have a couple more hurdles to jump in order to proceed.

The first—and most important—is that my most recent imaging needs to come back without any indication that I have cancer beyond my liver.

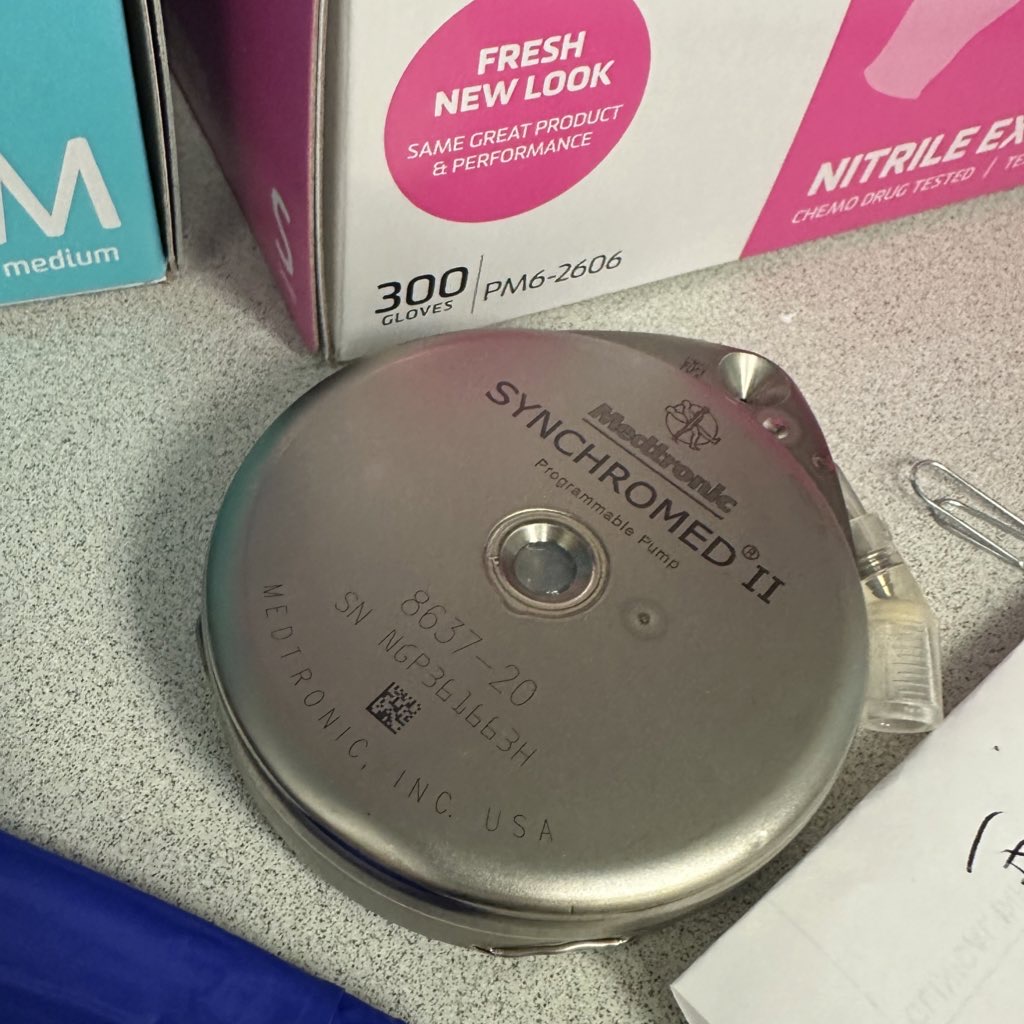

The second is that I have a successful pump implantation surgery. There is a relatively serious risk that, even after surgery, the pump will be unusable. This is the dice roll I’m willing to make.

I should know my surgery date within the next couple of weeks.

What’s a clinical trial?

There’s a misconception that clinical trials use patients as test subjects for unproven or dangerous treatments, but that couldn’t be further from the truth.

There are multiple types of clinical trial, each spanning a different facet of health. Prevention, diagnostics, screening, treatment, and supportive care can all have trials. These are tightly regulated and controlled.

These typically seek to answer one question: does the trial provide better outcomes than the current best option?

Of course, this is painting with a broad brush and doesn’t cover every single trial objective.

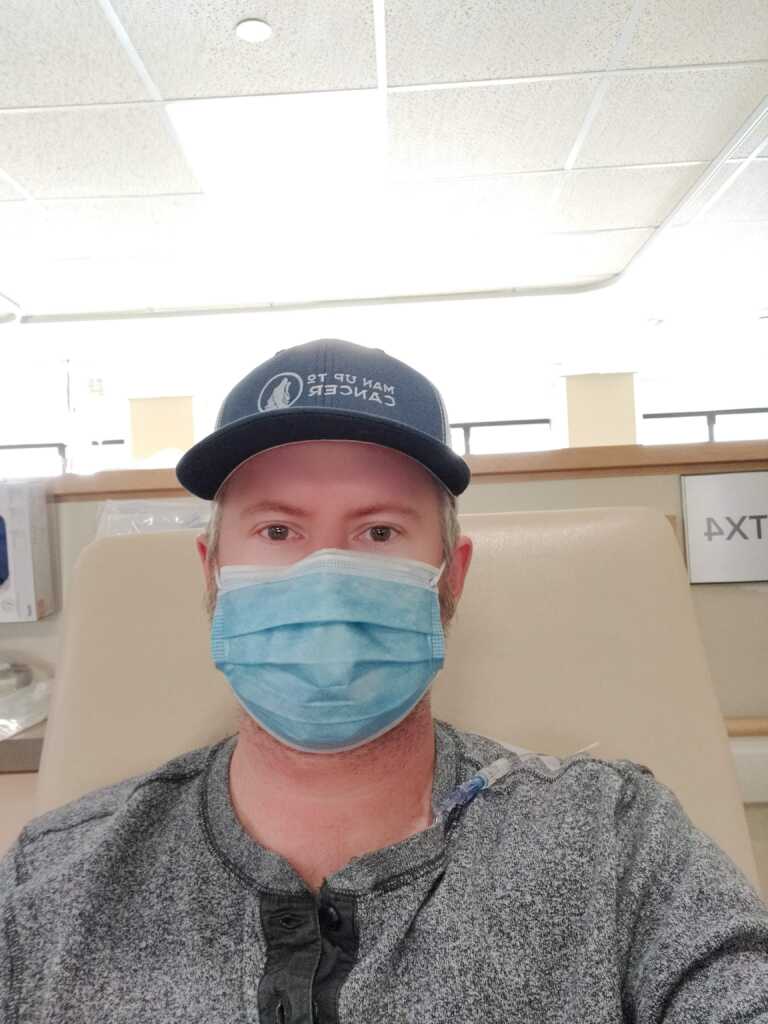

I’ll be participating in a Phase II trial; one of up to 100 participants. I’m patient 95. The purpose is to determine whether the liver pump is an effective treatment tool for metastatic colon cancer that has only spread to the liver.

This is the device that’ll deliver my treatment. It goes inside of me. It’s not a discman, in spite of appearances.

We’ll be taking a look at side effects, efficacy, toxicity, and some of key cancer stats like overall survival and time-to-progression. Cancer.ca has more details on clinical trials for those interested.

Suffice it to say that it’s a line of treatment that’s not available to everyone and, although it’s going to be a pain in the ass to make the 500km (310mi) round trip for treatment every two weeks, I think it’s the right call.

Choosing to participate

It’s worth noting that at the time of my cancer diagnosis, I was invited to participate in a trial that seeks to determine whether a combination of three drugs is as effective as a combination of four.

At the time, I declined because my aim was to work through treatment and the side effects profile of the trial drugs was incompatible with that goal. Colon cancer folks will understand the difference between FOLFOX, FOLFIRINOX, and FOLFIRI; the middle one being the drug combo for the trial.

Things have changed for me. Clinical trials are my only option for curative treatment at this point, so I’m weighing the pros and cons of participation against the alternative. I’d rather risk trial medication failing me than stick with standard treatment until it stops working (and it will stop working at some point).

In the case of the Hepatic Arterial Infusion trial: it’s a technique that has seen success in the United States and I’m confident that it’ll provide the results I’m looking for.

Again: the aim is to ultimately undergo a live donor liver transplant, but having the cancer cut out is an equally viable choice, too.

There is a cost to this. Financially, it means paying to travel to Toronto from Kingston every two weeks. Gas, food, and potential overnight stays don’t come cheap, but these are costs I’m willing to take on in order to participate.

I’m fortunate to have supportive people in my life who, through generously giving up spare bedrooms, kitchens, and more help minimize the financial impact.

Secondary benefits

One major benefit to participating in a clinical trial is that you’re under a microscope even more than when you’re receiving standard of care treatment.

For example, as part of my regular (systemic) treatment, I’m slated to receive imaging every six months. As part of the clinical trial, it’ll be every three.

I’ll be constantly surveilled to make sure that the drugs are working, that there’s no progression, and to see if my liver lesions are shrinking as intended.

My blood will be scrutinized bi-weekly at most to ensure that my organs are functioning correctly. I’ll continue to have an ER fast pass by way of my fever card in case I find myself in a pickle.

In addition to wanting to live, I want to provide an opportunity for my experience to benefit cancer patients in the future. One of the reasons that I’d like to participate in this specific trial is because I’m already a believer based on conversations with friends who’ve had same in the US.

I want this to be an option for more Canadians.

I don’t want people to have to travel to the only hospital in the country providing this cutting edge and lifesaving treatment. By participating, I hope that my data proves the efficacy and helps expand access to a novel treatment option.

Lastly, I think that by participating I’ll be able to look back and say that I did everything I was able to do in order to push back my cancer.

Next up: surgery

Now, the wait is on for a surgery date.

Between now and then, I’ll need to stop chemotherapy entirely for about a month to ensure that I’m in good shape to have my guts cut open again.

I’m expecting to be under the knife toward the end of September, with a two night stay in the ICU and about a month of recovery time.

It’s an exciting, scary time as I know the rug can be pulled at any time.

As the saying goes: it’s not over ’til it’s over.